Tischler Karpen: 1823-1871

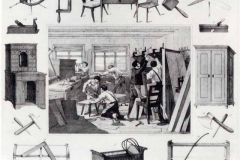

Playing among the shavings of the Old World shop, which possessed no woodworking machinery except a lathe, and employed but a handful of workmen… this eldest son imbibed the spirit of craftsmanship which comes only from generations of tradition…. —Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association. “The Story of Karpen.” Chicago: Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, August 26, 1930.

Family tradition is that the Karpen men were cabinetmakers, tischler, for generations. It was passed down that Moritz’s father, grandfather and great grandfather worked in that craft.[1]

DNA testing of the direct Karpen male line attests to the family’s Ashkenazi Jewish heritage. We do not know when the first Karpens migrated to the Kingdom of Poland and where they settled.

In the Kingdom of Poland, a “very large number of Jewish artisans…often lived on manorial demesnes in small towns and villages, along with Jewish merchants, to some extent assuming functions of the middle class, positioned between nobility and peasants. A considerable reservoir of Jewish craftsmen developed.”[2]

We cannot ascertain when the Karpen name was adopted by the family. The surname derived from the German word Karpfen, carp, a freshwater fish.[3] Karpen was an unusual name; records revealed only a few other Karpen families in the Prussian lands.[4] It was often misspelled as Karpon.

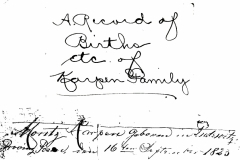

The first Karpen we know about is Moritz (Moriz) Karpen. He was born on September 16, 1823[5] in the village of Pudewitz, 14 miles (22 kilometers) east of the city of Posen (now Poznań). Then Pudewitz was part of Gnessen, Prussia; now it is Pobiedziska, Poznań, Wielkopolskie, Poland. In the late 1700s there were 144 houses and 796 inhabitants, of whom 84 were Jews. In 1811, there were 194 houses and 1071 people. In 1843, there were 140 houses and 1,450 inhabitants (720 Catholics, 399 Protestants and 331 Jews).[6] In 1834 an Elias Karpen, a trader and/or supplier, was listed as a naturalized citizen in the Province of Posen.[7]A synagogue and Jewish cemetery date from the eighteenth century. The synagogue was two blocks south of the town center (Rynek). The cemetery was about a mile southeast of the Rynek on a hillside above Lake Dobre; it was across the street from the Sacre Coeur Cloister.

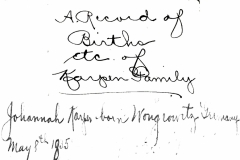

Sometime before 1857, Moritz Karpen moved from Pudewitz 35 miles (57 kilometers) north to Wongrowitz (Wongrowiz). Wongrowitz was 31 miles (60 kilometers) north of Posen; Posen was 168 (270 km) east of Berlin. Wongrowitz is now Wągrowiec, Wielkopolska Voivodeship (Greater Poland Province), Poland.

In the late fourteenth century, the Catholic Cistercian Order founded and owned Wongrowitz. The Cistercian abbot gave permission for certain non-Catholic merchants to do business in Wongrowitz. The Jewish small traders were not allowed to live in Wongrowitz. They lived in nearby villages (Chodzież [Kolmar] and Margonin) and would go to Wongrowitz to trade during the day.[8] In the second half of the 18th century the harsh restrictions were gradually lessened.

The three successive partitions of Poland 1772, 1793, and 1795 brought the geographical area of Wągrowiec, as part of the Province of Posen, under the control of the Kingdom of Prussia. Its name was changed to the German Wongrowitz. The town was developing economically. The Prussian government gave the town the designation of market town.[9] German became the civil language, and Jewish inhabitants rapidly learned the language. The laws regarding the Jews changed rapidly just after Partition of Poland in 1793.

About 1775 a small number of Jews moved from several of the neighboring towns (Rogasen, Schokken, Margonin, Gollantsch) to Wongrowitz.[10] No one could settle in a new town or village without the permission of the government. They were probably granted permission to settle in Wongrowitz with the hope that they would increase the tax base for the rulers.

Jewish people settling in Wongrowitz would have seen economic opportunities in the town. A history of the town from 1793, describes it as a spiritual town. It lies on the Welna River, over which the townspeople built a bridge. Most of the town was farmland. [11] The Jewish population grew from 4 people in 1780 to 134 Jews in 1800, when the town’s population was about 612. In 1816 there were 136 homes and 875 people, 628 Catholics, 167 Jews, and 80 Protestants. [12][13]

The King of Prussia gathered census information about the school children in the 1820s when there were 325 Jewish inhabitants. In the town, there were forty-five Jewish school-aged children. A Jewish school did not exist; thirty-seven Jewish children attended the public school. In the survey it was noted that the Jewish students were taught by a [Catholic] “not-converted teacher, who agreed with the rules of the religion.” [14] Christians and Jews paid to maintain that school. [15] In 1831, 2048 people including 543 Jews lived in Wongrowitz. [16][17]

In the 1836 tax list, a Moritz Karpen, cabinetmaker, was listed. He did not own any property or capital; he earned an annual trade income of about 200 Thaler. Those Jewish inhabitants who earned half that amount worked mostly as traders and tailors; a few were furriers, butchers, plumbers, bakers, watchmakers and carpenters. Those Jewish inhabitants who were higher taxpayers owned capital and property worth between 50 and 150 Thaler and earned between 250 and 900 Thaler. Most were merchants or tradesmen, and a few were distillers or bakers. The Rothmann family members, important merchants and community leaders, were listed among the highest taxpayers. This Moritz Karpen was in the middle class of taxpayers. [18]

We do not know if this was Moritz Karpen, a direct ancestor. Moritz would have only been thirteen years old in 1836. It could not have been his father as Jews of the German Ashkenazi tradition did not name their children after a living relative. It could have been an uncle or cousin.

Times were difficult in the 1840s. Epidemics of cholera decimated the population.[19] The Jews affiliated strongly with the German authorities rather than the Polish population, and the Poles resented their seemingly preferable treatment. In the 1840s in Wongrowitz, when Jewish inhabitants knew the moment they could obtain rights, they worked to improve their civil status. They supported the German politics, and they were treated as Germans. [20][21] Times were changing as the railroad reached Wongrowitz, and the farmers and young men began migrating to the towns and cities to find work.[22] By the 1860s, the town grew to 711 families. The 1861 census divided the population by religion: 1,930 Catholics, 761 Protestants, and 663 Jews. The same census also divided the population by nationality: 1,748 Poles, 943 Germans, and 663 Jews. [23]

Moritz Karpen married Johanna Cohn (Cohen) most probably in 1857. Johanna was born in Wongrowitz in 1835. The Cohen surname is that of those descended from the priestly class of ancient Israel; it is difficult to ascertain familial connections. Most certainly it was an arranged marriage as was the custom of the times. At age 34, Moritz was twelve years older than Johanna. This age difference was not uncommon as the husband needed to establish himself to support a family.

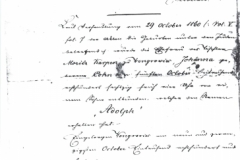

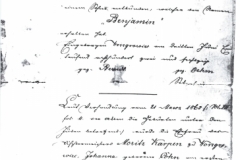

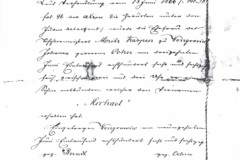

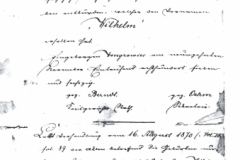

Between January 1858 and August 1870, Moritz and Johanna’s family grew rapidly. Johanna gave birth to Salamon (Solomon), Oscar, Adolpf (Adolph), Benjamin, Isaac, Michael, William (Wilhelm), and Leopold in twelve years.

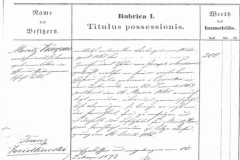

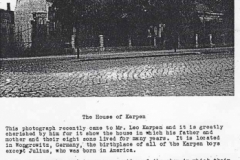

Moritz’s carpentry business must have prospered. In 1865 Moritz and Johanna “in marriage and in community property” purchased a property for 200 Thaler.[24] It was located close to the center of the town and one block from the railroad station (now Ul. Przemysłowa 5). Two substantial buildings were part of the property: the house and the building behind the house that served as the factory or workshop. In that small workshop, all of the furniture was made by hand as it was prior to 1871, and very little woodworking machinery was available. As the town was a small one, Moritz not only made all types of furniture for the home but also store fixtures and even coffins. [25]

In 1866, Moritz remained in the middle of the list of Jewish taxpayers; forty-five people were in a lower classification and sixty-two people were in the higher tax bracket.[26] Moritz Karpen was able to read and write in German. As late as 1863, documents revealed that a good number of the Jewish men signed the list with “ooo” indicating that they were unable to read and write. [27] Literacy was limited among the entire population.[28]

The 1870 tax census reported Moritz Karpen’s property and capital. The factory and house were valued 925 Thaler. The increase in property value might have been the result of the construction or expansion of his house and factory. Moritz’s trade income was 250 Thaler; this was not a large sum. He listed debts of 200 Thaler. The debts could have been from the purchase of the property or the costs of running his business. The official commented in the remarks column: “He has to feed a strong family.” [29] His eight children were all under twelve years old. Moritz could only turn to his eldest son, Solomon, to help him. “Under the personal guidance and teaching of his father, he had become, while yet a boy, a skilled cabinetmaker.[30] Still, Solomon was only twelve years old.

A Member of the Jewish Community

Moritz as a cabinetmaker was only part of the family’s history in Wongrowitz. Moritz was a member of the Jewish community and the documents, mostly written in German, revealed his involvement and what Jewish life was like for the Prussian Jews in the mid-nineteenth century.

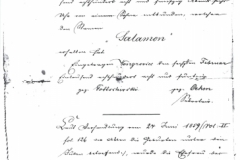

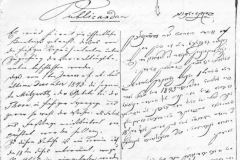

The Jewish community in Wongrowitz was typical of the Jewish communities that existed in the German-speaking lands. The Jewish community recorded important events and financial documents. Such a massive volume, Chevra-Kadische, exists from the middle of the eighteenth century. Community officials wrote in Hebrew, Judeo-German (German written in Hebrew letters), with numbers often written in Latin figures.[31]

When Jewish people settled in a new village or town, their first responsibility was to build a sanctified Jewish cemetery. In 1801 the Jewish community was given permission to have cemetery plot for a yearly fee of 3 Thaler.[32]It was located near Lake Durowskie, a short distance from the town center. According to Jewish custom, the deceased was buried in a simple pine box, most probably built by the Karpen craftsmen.

The Jewish community built a synagogue in 1807 near the town center. It burned down in 1824 and was reconstructed on the same site. The rustic design with a flat roof elevation was typical of synagogues built in the nineteenth century in rural areas. The building was 56 feet (17 meters) long by 47 feet (14.30 meters) wide. [33] The Wongrowitz synagogue complied with an unwritten rule, established over centuries living in Christian communities—that the church steeple would always be higher than other edifices, including the synagogue. The interior would have been designed with a niche for the Torah ark and reading lectern, bimah, on the Eastern wall and a special section on the side for women.

To support the construction of the synagogue, the Wongrowitz Jewish community made appeals to other Jewish communities for contributions. These collecte were frequent. The leaders compiled a list of donors and the amount contributed. Most people gave a few groschen with the total donation amounting to about 4 Thaler. Moritz Karpen would donate a few groschen; the Rothmanns were always the largest donors.[34][35] The Wongrowitz community most probably raised some funds in that manner. As was the custom, the Jewish community also sold the privilege of sitting on the synagogue benches. [36]

In the German-speaking lands, each Jewish head of household was automatically a member of the local Jewish community; each community was then under the bureaucratic control of the Oberrat of the Jewish communities, and above that authority the Oberrat the Prussian government.

In the early nineteenth century, the community was served by a rabbi who died in 1828. The community was fined for not telling the authorities the rabbi had died. They asked to have the fine waived and negotiated with the Oberrabbiner of Posen to have a new rabbi.[37] The next year, the Oberrabbiner Jacob Moses Eyer, approved Jacob Littauer’s appointment as rabbi in Wongrowitz.[38]Rabbi Littauer was the son-in-law of Abraham Eger, and the grandson-in-law of Akiba Eger.

Most of the Jewish children took lessons with the private Jewish teacher. These lessons were probably a few hours a week since the children attended the Christian public school. In 1828, of the sixty-three Jewish households, only fifteen had a little money; all the rest were very poor and could not pay to support a Jewish school. [39] In 1845 the Jewish community built a school in the market area.[40] Two years later the school was moved to the rabbi’s house near the synagogue.[41]

Jewish communities were ruled by royal decrees. Wongrowitz was under the royal government in Bromberg. The election of community representatives was governed by the royal government. It decreed that the announcement must be read in the synagogue and then posted on the door of the synagogue. When a collection was needed for the synagogue,the same process was followed. [42]

The community leader, vorsteher, was elected by the community members. Most often, one of the wealthier members would hold that office. In Wongrowitz, members of the extended Rothmann family, who were prosperous merchants, were chosen as leaders for many decades. [43][44][45]

The annual meeting to negotiate the community’s 1843 contract with Rabbi Littauer was announced in German and Judeo-German. The meeting was held in the house of community leader Rothmann.[46] The contract itself was written in German and Judeo-German with the numbers in Latin figures. The rabbi received salary of 100 Thaler, and his rent was paid by the community. In addition, he received payment for services rendered to individuals. A father of a circumcised baby boy would pay a small sum as would a bridegroom.47]

Moritz and his family attended synagogue on Friday nights and Saturday for Shabbat services. The synagogue was a few blocks from their house. In an amusing twist of history, a document has come down to us announcing that four people, including tischler Karpen, got into a fight and hit each other in the synagogue. The incident was reported to the government; [49] most probably the participants were fined.

The Karpen family observed all the Orthodox Jewish rituals. They kept a kosher home. On one Saturday evening, Tischler Karpen was a witness to the kosher slaughtering of an ox by the butcher. As customary, the certification of the kosher slaughtering was made by an authorized person. Karpen and others bought the kosher meat. [50]

To observe the rules of Shabbat and the other Jewish holidays, Moritz would have hired a Christian to light the candles in their home. In the same way, the Jewish community had a contract with a Christian to light the candles in the synagogue. [51] Johanna would have immersed herself in the ritual bath mikveh, at the appropriate times of the month. The Jewish community erected and administered the mikveh. [52]

In the 1840s the Jewish community set up a Jewish school that still served the children in the 1860s when the Karpen children would have attended. The fees were paid by the parents of the school children. The main teacher received a salary of 335 Thaler and 10 Thaler for rent; the second teacher made 195 Thaler plus 10 Thaler for rent. The teachers were paid more than the then Rabbi Gollstein who received a salary of 150 Thaler. [54] Cantor H. Löwenthal earned 75 Thaler. [55] Both the rabbi and cantor, however, would have earned additional fees for services rendered to individuals.

Such was the life of the Karpen family in 1870 when the political situation in the German states changed. The Franco-Prussian War 1870-1871 and then the formation of the Second German Reich brought Prussia, and consequently Wongrowitz, into the German nation. Migration to German cities like Berlin became an option for the Jews of Wongrowitz. It was an idea that certainly appealed to the wealthier merchants who wanted better opportunities for themselves and better education for their children. We do not know if Moritz ever considered such a move for his family.

We do know that in 1872 Moritz planned an even more momentous change.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY PRUSSIA

- Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, The Story of Karpen, (Chicago: Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, Aug. 26, 1930). ↑

- Michael Brenner, Stefi Jersch-Wenzel, and Michael A. Meyer. German-Jewish History in Modern Times: Emancipation and Acculturation, 1780-1871. (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1997), 65-66. ↑

- Alexander Beider, communication with Emily C. Rose, August 25, 2017. ↑

- Edward Luft, compiler. The Naturalized Jews of the Grand Duchy of Posen in 1834 and 1835 (Atlanta, Ga. : Scholars Press, 1987, revised 2004.) ↑

- Family Record and death certificate of Solomon Karpen. ↑

- pgsca.org/Reprints/Pobiedziska

- Hirschberg, Isidor. Verzeichniss sämmtilicher naturalisirten Israeliten im Grossherzogthum Posen (Bromberg: I. Hirschberg, 1836), 91. ↑

- Norbert Kron, “Jüdisches Leben in Wongrowitz vor 100 Jahren,” Posener Heimatblätter: Organ des Verbandes Posener Heimatvereine, Nr. 3, 12 Jahrgang, Marz, 1938.

- Translated from Gustawa Patro, Wągrowiec (Warsaw: Outline Histories, 1982), 53,60. ↑

- Heppner, Aron and J.Heppner, Aron and J. Herzberg. Aus Vergangenheit und Gegenwart der Juden und der jüdischen Gemeinden in den Posener Landen 2 Vols. (Breslau: Self-published, 1929), 1003-1009. ↑

- Translated from Gustawa Patro, Wągrowiec (Warsaw: Outline Histories, 1982), 53,60. ↑

- Heppner, Aron and J.Heppner, Aron and J. Herzberg. Aus Vergangenheit und Gegenwart der Juden und der jüdischen Gemeinden in den Posener Landen 2 Vols. (Breslau: Self-published, 1929), 1003-1009. ↑

- Translated from Gustawa Patro, Wągrowiec (Warsaw: Outline Histories, 1982), 53,60. ↑

- Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin; GStAPK, [I. Hauptabteilung], Rep. 76-III (Kulturministerium), Sekt.8, (Regierungs-Bezirk Bromberg), Abt. XVI (Sekten und Judensachen), Nr. 1, (Das israelitische Cultus- und Schulwesen), Bd. 1 (1823-1828); # 98 Table ↑

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wągrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 565; nr. Ap 14, 1828. Table. ↑

- Heppner, Aron and J.Heppner, Aron and J. Herzberg. Aus Vergangenheit und Gegenwart der Juden und der jüdischen Gemeinden in den Posener Landen 2 Vols. (Breslau: Self-published, 1929), 1003-1009. ↑

- Translated from Gustawa Patro, Wągrowiec (Warsaw: Outline Histories, 1982), 53,60. ↑

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wągrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 275; 114-125. Doc. # K-2017, April 1, 1836. ↑

- Translated from Gustawa Patro, Wągrowiec (Warsaw: Outline Histories, 1982), 53,60. ↑

- Heppner, Aron and J.Heppner, Aron and J. Herzberg. Aus Vergangenheit und Gegenwart der Juden und der jüdischen Gemeinden in den Posener Landen 2 Vols. (Breslau: Self-published, 1929), 1003-1009. ↑

- Translated from Gustawa Patro, Wągrowiec (Warsaw: Outline Histories, 1982), 53,60. ↑

- Translated from Gustawa Patro, Wągrowiec (Warsaw: Outline Histories, 1982), 53, 59, 60. ↑

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wągrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 212; nr. tabel Dec, 1861.

- October 14, 1845. Stadtarchiv Wągrowiec, Wągrowiec T. III-K. 263, p. 66. ↑

- Letter from Leo Karpen, Chicago, Illinois, March 1, 1948. ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, , Nr. 24, 9289 (Indent.- Nr. 9087); May 24, 1866, p. 216. ↑

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wągrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 276; 61-66 ; Feb 8, 1863, p. 61-65. ↑

- Wągrowiec Muzeum. ↑

- State Archive Posen, (Findbuch 4067, Laufzeit 1393-1801);Akta Miasta 17; Wągrowiec; sygnatura 10, nr. 268 . (2004 in Archive in Gniesgo), # 268 Moritz Karpen. ↑

- Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, The Story of Karpen Chicago: Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, August 26, 1930). ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, Nr. 19, 9284 (Indent.- Nr. 9082); 1731-1765. # 198. ↑

- Norbert Kron, “Jüdisches Leben in Wongrowitz vor 100 Jahren,” Posener Heimatblätter: Organ des Verbandes Posener Heimatvereine, Nr. 3, 12 Jahrgang, Marz, 1938. ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz; 92 (Indent.- Nr. 9081); 1876. ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, Nr. 1, 9267 (Indent.- Nr. 9064); Dec 27, 1857, p. 75. ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, Nr. 1, 9267 (Indent.- Nr. 9064); Nov 1, 1863 , # 95 . ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, Nr. 11, 9277 (Indent.- Nr. 9074); July 27, 1844. ↑

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wągrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 276; 1828, p. 3-13. ↑

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wągrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 276; 25 ; 10 Sep 1827 and 1829, p. 25. ↑

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wągrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 565; nr. Ap 14, 1828. Table. ↑

- Wągrowiec Muzeum ↑

- Wągrowiec Muzeum ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, Nr. 1, 9267 (Indent.- Nr. 9064); Jan 20, 1834 and last page: April 8, 1834. ↑

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wągrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 275; 114-125. Doc. # K-2017, April 1, 1836. ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, Nr. 1, 9267 (Indent.- Nr. 9064); Dec 27, 1857, p. 75. ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz; Nr.31, 9300 (Indent.- Nr. 9095); Dec 7, 1843, # 59 ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz; Nr.31, 9300 (Indent.- Nr. 9095); Dec 7, 1843, # 59 ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, Nr.31, 9300 (Indent.- Nr. 9095); 1843. ↑

- Photo: Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz; 92 (Indent.- Nr. 9081); 1876. ↑

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wągrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 281; 3110 [crossed-out]; Oct 8, 1861. ↑

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wągrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 281; Feb 5, 1862. ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz; 9302 Nr. 34 (Indent.- Nr. 9098); 1843, # 34 ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz; 92 (Indent.- Nr. 9081); 1876. ↑

- Photo: Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, Nr.31, 9300 (Indent.- Nr. 9095); December 11, 1842. ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, , Nr. 24, 9289 (Indent.- Nr. 9087); Dec. 1, 1866, # 20 (57) ↑

- Archiv der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum; 1,75 A Gesamtarchiv, Jüdische Gemeinden; Wo 3 Wongrowitz, , Nr. 24, 9289 (Indent.- Nr. 9087); Dec. 7, 1866, # 11 (58) ↑