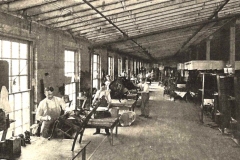

The Manufacturing Process: 1900-1910

Give your customers all that you promise— and maybe a little more. Don’t skimp. — Solomon Karpen in Neil Clark, “How Nine Brothers Built Up a $10,000,000 Business,” Forbes, August 1, 1926, 11. Private collection, Emily C. Rose.

Solomon Karpen’s motto was: “What a man pays for, he shall get.”— Letter, Mrs. Solomon Karpen (Ernestine) to her great granddaughter, January 17, 1952. Private collection, Emily C. Rose.

Solomon, Oscar, and Isaac Karpen devoted years of expertise and experience to manufacturing furniture that carried the family name. This was a massive ongoing endeavor. In its catalogs and advertisements, Karpen Bros. continually explained to the public and the dealers the long process entailed from lumber in the forest to finished furniture in the salesroom.

Purchasing

Solomon was in charge of purchasing. Prior to 1906, only three people were in the purchasing department. The story was told decades later that Morris “Morrie” Rauh was working for B. Kuppenhimer & Co. clothiers when he and “Mr. S. K.” were boon companions on a fishing trip. The fish was biting good, and between bites, Mr. S. K. inquired “how would you like to work for me?” Morrie replied, “I am always looking to better myself.”[1] As well as working for Karpen Bros., Morrie became a close friend of the family.

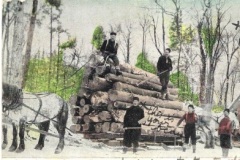

Once Karpen Bros. acquired its own frame factory in 1887, it purchased huge quantities of lumber that was shipped by water and rail to the factory.

The Woods

In special informative articles in its catalogs, Karpen Bros. described that facet of the business in detail:

Cuban Mahogany (Swietenia mahagoni):

The Mahogany Tree, Scientific American, March 3, 1917, 136-138.

Oak (Quercus)

New carving machines were hailed for their efficiency and cost-savings attributes. Another result of their introduction was the increase use of certain woods that previously had been unsuitable for making furniture. Woods like ash and birch were being used for factory-made furniture.[2] These cheaper woods were then stained to resemble mahogany, the more expensive wood used for fine hand-carved furniture.

Birch (Betula)

Walnut (Juglans regia)

Rare Woods

Selecting and Drying the Wood

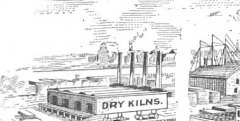

“The selection of wood for the Karpen factories is in the hands of an expert and purchases are made six months and a year ahead, so that the lumber is thoroughly seasoned and dried before it is used.”[3] The lumber was then seasoned: “The capacity of the dry kilns is 280,000 feet per day, and as the plant is conveniently located near the river, lumber will be received from vessels traversing the lake route.”[4]

“Lumber is now split up into many subdivided grades, the number being astonishingly wide to one not posted in the business. A piece of timber might be really genuine mahogany, while it was nevertheless of a cheap quality and grade. The market supplies multiplied grades in various woods, but in every instance all lumber or timber which is to be worked up into Karpen Furniture must be the best of its class, clear and free from the slightest defect of knot, warp, split check or wormhole….”[5]

“Not only is Karpen lumber of a perfect quality, but it is also doubly seasoned. It is first dried by natural means through years of exposure to the sun and wind. Before going into the factory it is finally passed through a battery of scientific dry kilns in which every atom of sap or moisture is evaporated by powerful currents of superheated dry air.

“The Karpen dry-kiln plant is extensive and Karpen owned. The firm do their own work on their own premises and do not send it out, as is the very general custom of furniture manufacturers who do not possess such facilities.”[6]

Wood Carving and Frames

Oscar was in charge of the Frame Factory. Prior to the early years of the twentieth century all the wood carving was done by simple hand tools.

The automatic wood carving machine changed that technique. In its catalog, Karpen Bros. described an example of the carving process for an ornate piece:

The history of this parlor suite began when the artist selected as his motif the beautiful blossom of the Orchid Catillya. With the flower continually before him the artist molded in clay the entire framework of the suite, every detail of which is in perfect harmony with the orchid which served as his model and inspiration. The making of the plaster cast from the clay model and the reproduction of the plaster cast in wood was the work of many months of artistic effort.[7]

Much of the work, however, was still done by highly trained, experienced carvers.

Karpen Bros.’ wood frames were made to last: every part was “doubly braced and strengthened to secure a firm and durable foundation for the Karpen springwork.”[8] Glue for the frames was manufactured from the hides and other by-products of animals slaughtered in Chicago’s immense stockyards.[9]

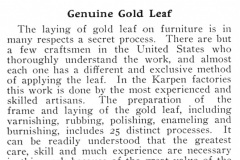

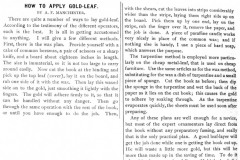

The Art of Hardwood Finishing

The next step in the manufacturing process was applying the correct finish to the furniture frame. It was Oscar who was the master of finishing. From his early training, he became an expert in laying gold leaf, and he was in charge of the craftsmen. The Karpen Bros. catalogs explained the various processes to the dealers and customers:

Gold Leaf Finish and Metal Leaf Finish:

Mahogany Finish:

Birch with a Mahogany Finish:

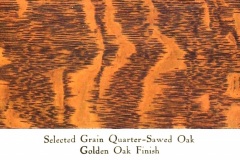

Oak Finished with Golden Oak:

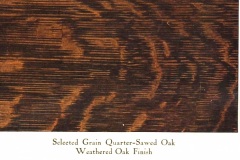

Oak Finished Weathered Oak:

Oak Finished Antwerp Oak:

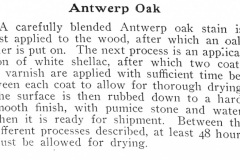

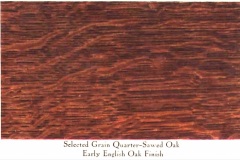

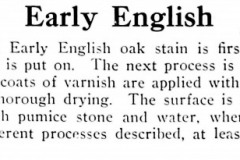

Oak Finished Early English Oak:

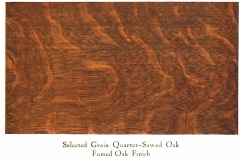

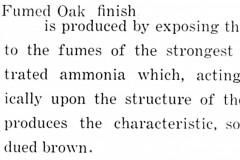

Oak Finished Fumed Oak:

Veneers

New machines also produced very thin wood veneers.

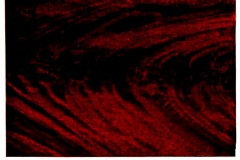

Crotched Mahogany Veneer:

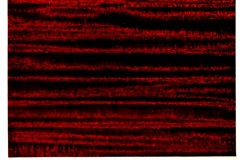

Striped Cuban Mahogany Veneer

In its advertisements, Karpen Bros. highlighted pieces made from highly polished to a “fine piano polish finish” Cuban mahogany[10] and quartered-sawed oak. [11] Occasionally a piece created from French walnut was displayed. [12] It frequently mentioned that its factory adequately seasoned all wood used. [13] The advertising copy often described the specific finish applied to the piece shown be it gold leaf,[14] or the various oak finishes. [15][16] The less expensive pieces advertised usually were of red birch “beautifully finished in gold leaf of dull, antique gold or burnished effects” [17] or “birch with mahogany polished finish.” [18]

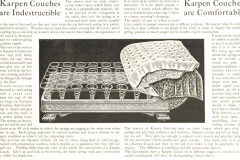

Springwork

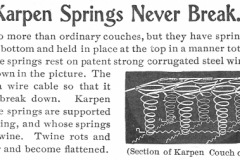

In the 19th century, the springwork construction of furniture was not durable:

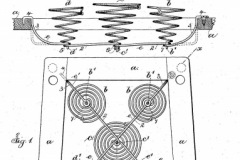

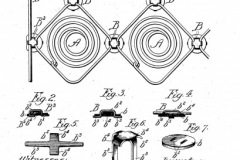

Karpen Bros. was relentless in its emphasis on good quality spring work. In the 1890s Karpen Bros. had patents (which have not been located) on several spring innovations. In the mid to late 1890s the company began using springwork patented by John A. Staples and used by Staples & Hanford located in Newburgh, New York (application filed October 19, 1891, patented May 10,1892):

J. A. Staples of Staples & Hanford Patent US474536, May 10,1892.

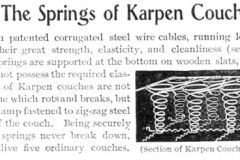

Karpen Bros. took considerable space in its catalogs and advertisements to illustrate and describe its springwork:

Other advertisements over the course of many years included short references to the Karpen springwork feature:

“The springwork is the Karpen Guaranteed Construction, the most elastic and comfortable and will never wear out.” [19]

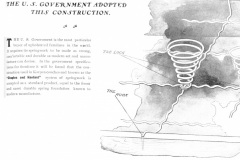

“The spring work is the Karpen Guaranteed Construction used by the U.S. Government.”[20]

“The springs of Karpen furniture do not rest on wood or webbing as in the case of ordinary upholstered furniture. They are supported by steel corrugated cables, known as Karpen guaranteed spring construction, such as is specified by the U.S. Government in all its upholstery work.” [21]

“Karpen furniture is built on the famous Karpen guaranteed construction selected as the standard by the U. S. Gov’t because it produces the best foundation for upholstery.” [22]

“The spring work is that famous Karpen Guaranteed Construction which the U.S. Government has adopted in all its upholstery work.” [23]

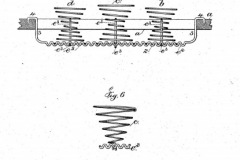

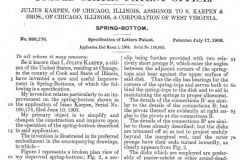

For several years Karpen Bros. worked on improvements to the springwork. In 1903, Isaac filed an application for the spring-bottom (Serial No. 160,174, June 10, 1903). Julius then filed a patent application improving Isaac’s construction which he assigned to S. Karpen & Bros. (Patent US826170, application filed March 1, 1904; patented July 17, 1906.)

Karpen Spring-Bottom Patent US 826170, July 17, 1906.

The company called its innovation “Karpen Square Top Spring Construction.”

Quality Stuffing

Excelsior:

The coverings of the metal springs and the stuffing of the cushions contributed to the quality of Karpen Bros.’ pieces. Ever ready to point out the poor quality of its competition’s furniture, it wrote in advertisements that it never used excelsior (thin wood shavings, sometimes called wood wool) “or other cheap substitute.” [24]

Moss:

Straw:

Horsehair and Curled Hair:

In the early years, cushions were filled with “fine quality genuine, pure black [horse] hair and southern black moss.” [25] Horse hair, the manes and tails of deceased horses, was quite expensive. It was often used as the top-most layer.

Then only the “finest curled hair” [26] was used because it gave “a luxurious, yielding, seating quality.” [27] Curled hair was the by-product hogs slaughtered in Chicago’s stockyards. In some advertisements, the copy added the phrase “thoroughly purified” to clarify the treatment of the hair. [28] “Curled black genuine hair [was layered] over Florida [black] Moss.[29]

Cotton:

Cushions and many pieces were filled “pure white felt, soft and durable” [30]

Karpen Bros.’ commitment to quality construction became the basis for its business model and marketing strategies.

Note: In these years, some materials in S. Karpen & Bros.’ catalogs were similar. Content and presentation varied slightly as did the location of the pages in the catalog. All catalogs written and published by S. Karpen & Bros. Catalog dimensions: ca. 11 inches by 15 inches. All private collection, Emily C. Rose.

The catalogs and pages referenced regarding Woods, Finishes, and Wood Information are:

49th Semi Annual Catalogue. 1904, bef. 4. 50th Semi-Annual Catalogue. 1905, aft. 4. 26th Annual Catalogue. 1906, aft. 4. 27th Annual Catalogue. 1907, bef. 6. 28th Annual Catalogue. 1908, 5-6. 29th Annual Catalogue. 1909, 36-7.

The catalogs and pages referenced regarding Springs and Springwork are:

49th Semi Annual Catalogue. 1904, 128. 50th Semi-Annual Catalogue. 1905, 74. 26th Annual Catalogue. 1906, 106. 27th Annual Catalogue. 1907, 97. 28th Annual Catalogue. 1908, 219. 29th Annual Catalogue. 1909, 207.

- S. Karpen & Bros., “Karpen’s Hall of Fame: Twenty Years of Faithful Service [Morrie Rauh],” Karpen Komment, Sept. 1926. ↑

- Furniture World, Aug. 15, 1901, 5. ↑

- S. Karpen & Bros., 50th Semi-Annual Catalogue, 1905, (Chicago: S. Karpen & Bros., 1905), [4]. ↑

- Furniture World, Apr. 27, 1899, 21. ↑

- S. Karpen & Bros., 29th Annual Catalogue, 1909, (Chicago: S. Karpen & Bros., 1909), 37. Private collection, Emily C. Rose. ↑

- S. Karpen & Bros., 29th Annual Catalogue, 1909, (Chicago: S. Karpen & Bros., 1909), 37. ↑

- S. Karpen & Bros., 50th Semi-Annual Catalogue, 1905. (Chicago: S. Karpen & Bros., 1905), 20. ↑

- Munsey’s Magazine, Dec. 1902. ↑

- Sharon Darling, Chicago Furniture: Art, Craft, & Industry 1833-1983. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 1984), 46.↑

- McClure’s Magazine, June 1901, 62. ↑

- Ladies Home Journal, Mar. 1909, 81. ↑

- Munsey’s Magazine, Aug. 1908. ↑

- The Furniture Journal, Nov. 10, 1909, inside cover. Munsey’s Magazine, Dec. 1902. ↑

- Munsey’s Magazine, Aug. 1908. ↑

- McClure’s Magazine, Mar. 1902, 90. ↑

- McClure’s Magazine, Jan. 1902, 30. ↑

- McClure’s Magazine, Mar. 1902, 90. ↑

- McClure’s Magazine, Jan. 1902, 30. ↑

- Munsey’s Magazine, Apr. 1901. ↑

- Munsey’s Magazine, Nov. 1901. ↑

- Ladies Home Journal, Oct. 1902, 42. ↑

- Munsey’s Magazine, Dec. 1902. ↑

- McClure’s Magazine, Jan. 1902, 30. ↑

- Furniture Journal, Nov. 10, 1909, inside cover. ↑

- S. Karpen & Bros., Upholstered Furniture, (Chicago: S. Karpen & Bros., 1897), 6. Munsey’s Magazine, Apr. 1901. McClure’s Magazine, 1901. McClure’s Magazine, Jan. 1902, 30. Munsey’s Magazine, Nov. 1901. ↑

- McClure’s Magazine, Nov. 1902, 78. McClure’s Magazine, Dec. 1902. ↑

- Numerous mentions in S. Karpen & Bros.’ catalogs. Saturday Evening Post, Oct. 2, 1909, 40-41. ↑

- Munsey’s Magazine, June 1907. Saturday Evening Post, Feb. 16, 1907, inside front cover. Munsey’s Magazine, Feb. 1907. Munsey’s Magazine, June 1907) . ↑

- Everybody’s Magazine, Oct. 1911, 106; Cosmopolitan Magazine, Nov. 1911, 120G. Saturday Evening Post, Oct. 28, 1911. Literary Digest, Oct. 21, 1911, 702. ↑

- McClure’s Magazine Feb. 1902, 31. McClure’s Magazine Mar. 1902, 90. ↑